Mariam Nimer Mahmoud was only a few months old when she and her family first arrived in Beirut. They were handed a tent and some food by the U.N. - “lentils, rice and sugar,” she said.

Her parents told her they were staying for a week, and would then go back. “We were sitting on the sand and mud waiting to see what would happen to us.”

It was 1948, the year of the Nakba, or catastrophe.

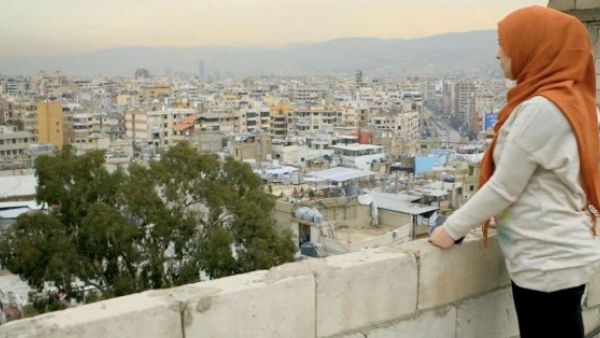

Today Mahmoud still lives in the camp, and is a regular attendee of Social Support Society, an organization that cares for the elderly in Burj al-Barajneh, one of the 12 Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon.

There she takes part in weekly activities like writing, reading and drawing that aim to help the elderly with their mental abilities.

A lot has changed in Burj al-Barajneh since Mahmoud arrived. “Of course there was no electricity. We had no bathrooms, no toilets. They existed outside of our houses,” she told The Daily Star. But the area rapidly transformed into a concrete sprawl, and it is now home to over 20,000 Palestinian refugees.

The Social Support Society was one of a dozen locations visited Monday by the U.K.-based Palestinian Return Center as part of efforts to draw international attention to the quality of life of Palestinian refugees living in Lebanon.

Their visit was part of an ongoing response to the United States’ decision to cut all contributions to the U.N. Palestinian refugee agency, leaving UNRWA and multiple local organizations that rely on its support in a state of insecurity. The first visit the PRC made was to a UNRWA-run primary school called Haifa.

“UNRWA has played the biggest role in the life of the Palestinians. This is why we are fighting by all means for UNRWA to exist. We want to see our children and grandchildren grow up in a better way - a better life, with dignity,” said UNRWA’s chief area officer for Beirut Mohammed Khaled, who was on the visit.

“We’re not going anywhere until a final and just solution is found for Palestinian refugee problems,” Hoda Samra Souaiby, a spokesperson for UNRWA, said.

“The first of September we opened our schools, and everybody knows we had [only enough] resources to run for one month. ... We didn’t know until the end of August whether the schools would open or not,” Souaiby added. “After September we secured money for October, then November and December, and now here we are.”

Hayat Saleh, the Arabic teacher at Haifa, said one of the school’s biggest problems was the number of students in each class, which she said in some cases reached up to 40, leaving almost no place in the classrooms for teachers to stand.

In the years preceding the U.S. decision to halt its funding to UNRWA, the country provided nearly 30 percent of the agency’s funding.

Although other countries responded by increasing their funding to the organization, UNRWA’s Director in Lebanon Claudio Cordone said Monday that funding remained a serious issue.

Other stops on the PRC’s schedule included an UNRWA-funded clinic and Soufra, an all-female social enterprise launched by Mariam al-Shaar, who has spent her whole life in Burj al-Barajneh. Shaar opened her own catering business based in the camp, run entirely by women there, which she later expanded into a food truck business. Her next step is to teach women how to drive so they can operate the trucks themselves.

Back at Social Support Society, Mahmoud reflected on life in Lebanon. “Are we happy with our lives? No. We are refugees. The name ‘refugee’ is as frustrating as the name ‘Palestinian.’”

She said she kept up her connection to Palestine through daily practices like cooking and embroidery, taught to her by her mother. Now, Mahmoud teaches her daughter embroidery. Because there is no electricity, they do it by candlelight.

Mahmoud hasn’t lost her determination to return. “I’m going back,” she said. “Even if there were no houses, I would sleep on the ground.”

This article has been adapted from its original source.