The results of two national elections in Iran last week may signal a victory for reformists and some moderates who favor expanding social freedoms and engagement with the West, but their influence remains limited.

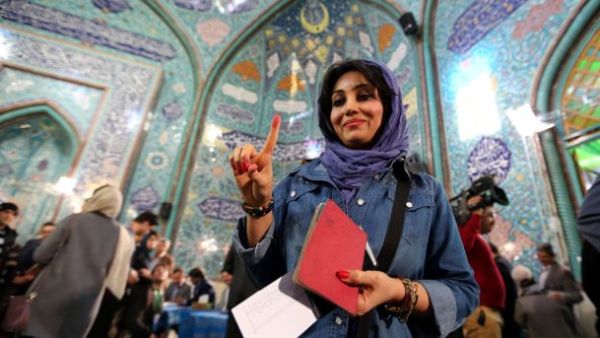

The elections were the first since Iran agreed in July to limit its nuclear program in exchange for the lifting of sanctions. Some saw the elections as a referendum on President Hassan Rouhani, who campaigned on a platform of greater cooperation with the Western world.

First, here’s what happened: In the first election, which was for the 290-seat Iranian parliament, reformist lawmakers snagged at least 85 seats at the time of writing. Meanwhile, moderate conservatives won an additional 73 seats. Their combined majority means that the two blocs will outnumber the hard-liners and conservatives who oppose the nuclear deal and Rouhani’s plans to push for greater social freedoms. (Conservatives won just 68 seats, a drop of 44 from the current parliament.)

A reformist-moderate majority in parliament could allow Rouhani greater ability to pass the kinds of laws he favors. "If there is a Majlis [parliament] less antagonistic toward Rouhani, it could be an ally in his conflicts with the Revolutionary Guard…[and] that would allow him to move his agenda forward,” Mohammad Ayatollahi Tabaar, a scholar of Iranian politics at Texas A&M University, told the Council On Foreign Relations. “I think his ultimate goal is to reestablish relations with the U.S."

Moderates also performed well in a separate election for the 88-seat Assembly Of Experts, the body which may soon be in charge of appointing the next Supreme Leader of Iran. (At 76, Ayatollah Khomeini is no longer a young man.) A list of candidates promoted by moderates captured all but one of Tehran’s 16 seats on the panel, while two of its most extreme clerics lost their seats, according multiple reports.

But Iran’s evolution towards becoming a more open, free nation--if it’s happening at all--is progressing slowly. “Despite winning the elections, the reformers are not able to intervene in Iran's foreign policy, especially policies which relate to Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Bahrain, and Lebanon,” noted an Arabic-language analysis of the elections in Arabi21, Gulf-based news outlet, which was translated by Al Bawaba staff.

In other words, Iran’s hard-liners are still pulling the strings of some of the Islamic Republic’s most important institutions.

What’s more, some of the so-called reformists and moderates who were elected may not be as progressive as they sound. Last month, a huge number of reformist candidates were prevented from running: Iran’s Guardian Council, which decides who is fit to run and who’s not, failed to qualify a whopping 99 percent of the 3,000 reformists who wished to throw their hats into the ring, The Guardian reported.

That may have given an opportunity for one-time conservatives to re-cast themselves as moderates: For example, Mohammad Mohammadi Reyshahri and Ghorbanali Dorri-Najafabadi--two former intelligence ministers who are accused by the opposition of having dissidents murdered--ended up running on the list endorsed by Rouhani for the Assembly of Experts, according to Bloomberg View foreign affairs columnist Eli Lake.

Lake also pointed out that Kazem Jalali, a hard-liner who has called for sentencing to death two leaders of the Green Movement, which demanded the resignation of former Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad after the 2009 elections, ran on the list endorsed by reformists for the parliament.

If change is afoot in Iran--if the Islamic Republic is indeed emerging from decades of isolation into greater dialogue with the West, and shrugging off some of the social restrictions that have been in place since the 1979 revolution--it may yet be a while before Iranian citizens feel its effects.

By Hunter Stuart