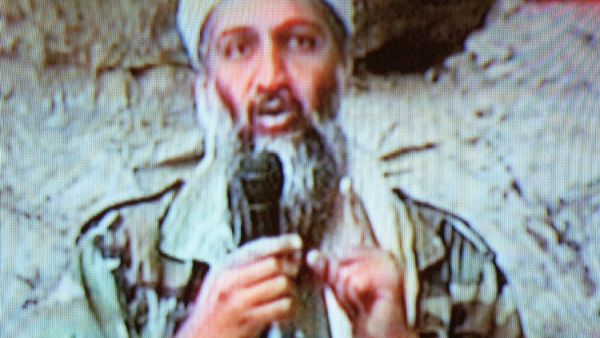

Building on my piece last week, I ask: What does a post-Osama world look like? Osama Bin Laden was a by-product of one of the most antagonistic conflicts in recent history. After all, when was the last time anyone openly called a country they were at conflict with an ‘evil empire' without raising the slightest sense of sarcasm or question?

Imagine living through a time when the world as a whole took such moral accusations at face value. The late Ronald Reagan gave the famous ‘evil empire' speech in 1983, only three years after the second instalment of George Lucas's successful franchise Star Wars V: The Empire Strikes Back. But it was the eighties and the world was different then.

Read special section on Osama Bin Laden

Back then the USSR was evil and the US thought jihad was cool. It exported stuff, made in China was cheap and Sony was awesome. Now Russia, still not cool, is more capitalist than the US. Osama is dead, Al Qaida is no longer an existential threat and jihad against civilians is globally condemned and opposed. The US runs a trade deficit, China runs a surplus and Sony is no longer awesome... Samsung is.

Welcome to the 21st century, more 12th than 20th, where no singular power runs the world but a balance of those powers does, as Parag Khanna notes. It is also a G-zero century where China doesn't care to shoulder the political responsibilities that come with its economic prosperity of co-policing the world with America — forming a G2 — and the EU and Japan have just as much internal woes as the US does — to form a G3 — observes Nouriel Roubini.

Conflicts

One of the reasons why the more recent prequel trilogy of Star Wars — episodes I, II and III — didn't do as well as the original is because the analogy was lost on Generation Y. This new generation doesn't gravitate to the values of antagonistic infallibility but one of a post-ideological world. Film makers are learning the hard way to create more conflicted torn superheroes than previously unflinching ones — case in point: Superman recently gave up his US citizenship and has proclaimed himself a citizen of the world.

The idea of conflicts, driven by ethnicity, race and creed, isn't proving to be as attractive a notion to Generation Y as it did to their parents. If anything, the notion of ‘us' versus ‘them' is provincial really. Something only the uninspiring would subscribe to.

It speaks of an era when ‘we' were all uniformly standard in our aspirations, views and mistrust towards the other and ‘they' were equally unanimous in their aspiration to destroy us. Criticising this proposition is no longer reserved to the leftist Chomskys of this world.

In fact, the pragmatic post-partisan proposition of radical centrism has only finally started to gather pace now. Google's Eric Schmidt now chairs the New America Foundation think-tank, one of the most prominent radical centrist institutions, and its board includes Francis Fukuyama and Fareed Zakaria.

This century isn't meant to be a polarised one. China, Russia, India, the US, the UK, the EU, Japan and Brazil won't always agree but their aspirations will control, deter and balance each other. The Turkeys and South Koreas of this world will learn to be even more over-achievers than they've become.

The Saudis of this world, should they aim to remain significant, will have to quickly reinvent themselves. This trend of nuance is what defines the Arab Spring. There is a new notion of engaging instead of alienating those at the fringe. The more politically, economically and culturally entrenched groups are together the more likely it is that peace, liberty and prosperity may be achieved.

Reactionaries

And so in this sea of change where pragmatism trumps ideology and ambition trumps anxiety, what are the prospects for an Arab renaissance? Could we perhaps realise that we need not repeat the propping up when convenient and ostracising when not so convenient of proxies? Could we not be reactionaries?

This is the century when the term pre-emption, one that former US president George W. Bush hijacked in the last decade, will mean engagement not offence. Those who we choose not to speak to won't disappear. We have seen what ostracising Syria has done.

For all the years during which former Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak, and his two predecessors, combated the Muslim Brotherhood, the party only grew. It wasn't their ideology but their support network that served as a substitute to the failings of the state in providing social services that kept the party from disintegrating and even thriving. Engagement and political entrenchment will do more to neutralise any possibilities of an Islamist state than any effort, however monumental, to ostracise them.

This is what Generation Y wants to see from its leadership: a nuanced approach to a multi-polar world. No more talk about ‘good guys' and ‘bad guys', just guys trying to get up in the world; a world where the pragmatism of the pursuit of prosperity overtakes that of ideological conflict. Welcome to a post-Osama world, one that favours nuanced subtext over rhetorical noise.

Mishaal Al Gergawi is an Emirati current affairs commentator.